Caribbean Matters is a weekly series from Daily Kos. Hope you’ll join us here every Saturday. If you are unfamiliar with the region, check out Caribbean Matters: Getting to know the countries of the Caribbean.

We enter Black History Month this year filled with uncertainty. It’s unclear how the newly elected government led by President Donald Trump and his appointees will attempt to limit or erase annual celebrations which have been in place since Dr. Carter G. Woodson initiated Negro History Week in 1926. This unease isn’t new, given right-wing efforts to ban teaching Black history and remove books from school curriculum and libraries.

The contributions of Caribbean Americans to our history are an important part of our story that should not be overlooked, and those of you who are teachers or who have children at home can resist the efforts at erasure by utilizing resources that are available online.

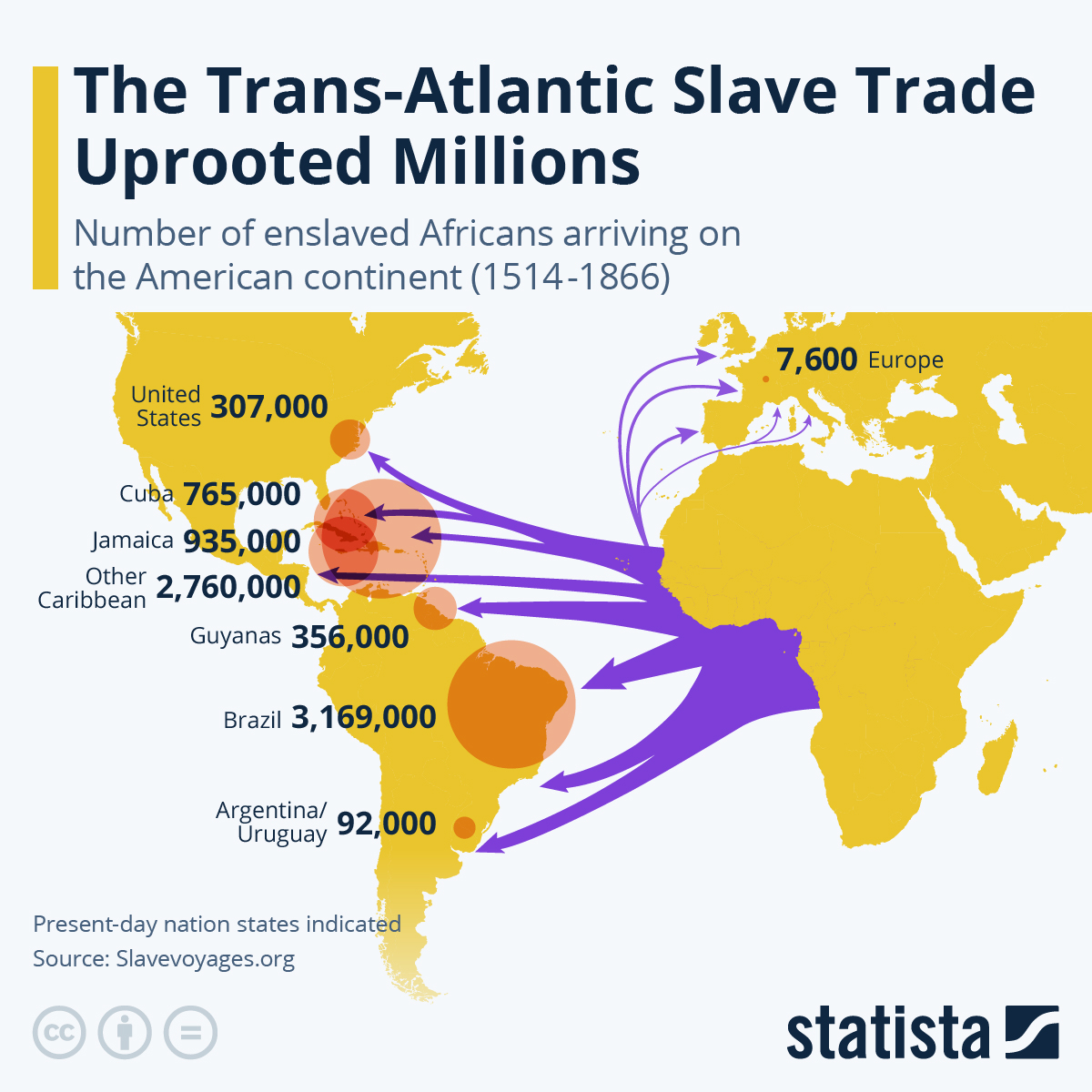

Let’s start at the beginning. The advent of massive numbers of Black people to the Caribbean and the Americas began with the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. Contrary to how many people in the U.S. may view that history, the vast majority of enslaved Africans were not brought to America.

Statistica has posted a simplified map:

Statistica data journalist Katharina Buchholz gives some background to the map:

400 years ago, in August 1619, the first ship with enslaved Africans destined for the United States arrived in what was then the colony of Virginia. But the cruel history of the trans-Atlantic slave trade begins much earlier and goes on much longer – for more than 350 years.

In fact, many enslaved people lived in the English colonies in North America before that date. They came to the present-day U.S. via Spanish and Portuguese colonies, where enslaved Africans arrived as early as 1514, or were transferred as bounty from Spanish or Portuguese ships.

The United States are heavily associated with slavery and the capture and forceful relocation of Africans. Around 300,000 disembarked in the U.S. directly, while many more arrived via the inter-American slave trade from the Caribbean or Latin America. It is estimated that almost 4.5 million enslaved Africans arrived in the Caribbean and another 3.2 million in present-day Brazil.

Professor Henry Louis Gates wrote for The Root back in 2014 about how many slaves actually landed in the U.S.:

Perhaps you, like me, were raised essentially to think of the slave experience primarily in terms of our black ancestors here in the United States. In other words, slavery was primarily about us, right, from Crispus Attucks and Phillis Wheatley, Benjamin Banneker and Richard Allen, all the way to Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth and Frederick Douglass. Think of this as an instance of what we might think of as African-American exceptionalism. (In other words, if it's in "the black Experience," it's got to be about black Americans.) Well, think again.

The most comprehensive analysis of shipping records over the course of the slave trade is the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, edited by professors David Eltis and David Richardson. (While the editors are careful to say that all of their figures are estimates, I believe that they are the best estimates that we have, the proverbial "gold standard" in the field of the study of the slave trade.) Between 1525 and 1866, in the entire history of the slave trade to the New World, according to the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, 12.5 million Africans were shipped to the New World. 10.7 million survived the dreaded Middle Passage, disembarking in North America, the Caribbean and South America.

And how many of these 10.7 million Africans were shipped directly to North America? Only about 388,000. That's right: a tiny percentage.

This JAM60 article, from 2022 makes an important point about historical connections:

People from the Caribbean were taken to America in 17th century as slaves. The beginnings of a strong Caribbean community was established in South Carolina and Virginia by British slave masters who took slaves from Barbados around 1650. The majority of South Carolina’s slaves were from Barbados up to 1750. It was estimated that as high as 20 percent of South Carolina’s slaves were from the Caribbean. The majority of slaves living in the north states were also of Caribbean origin. Slaves from New York were three times more likely to be from the Caribbean than those from Africa.

The Migration Policy Institute covers contemporary data on Caribbean immigrants in the U.S.:

Voluntary, large-scale migration from the Caribbean to the United States began in the first half of the 20th century, following the end of the Spanish-American War, when a defeated Spain renounced its claims to Cuba and, among other acts, ceded Puerto Rico to the United States. In the early 1900s, U.S. firms employed Caribbean workers to help build the Panama Canal, and many of these migrants later settled in New York. A high demand for labor among U.S. fruit harvesting industries drew additional labor migrants, particularly to Florida. After World War II, U.S. companies heavily recruited thousands of English-speaking “W2” contract workers from the Bahamas, Jamaica, and Barbados to fill critical jobs in health care and agriculture. Around the same time, political instability in Cuba, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic fueled emigration from the region. Following the 1959 Cuban Revolution, an estimated 1.4 million people fled to the United States. Whereas the first major migration of immigrants from Cuba, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and other Caribbean nations was comprised mostly of the members of the elite and skilled professionals, the subsequent flows consisted chiefly of their family members and working-class individuals.

CBS New York posted this feature on Caribbean immigrants arriving via Ellis Island. While millions of immigrants from Europe and Asia arrived through Ellis Island, hundreds of thousands of Black people entered from the Caribbean as well:

Policy Analyst Dr. Valerie Lacarte in a post for the Sustainable Development and Climate Change blog points out the contributions of Caribbean Americans.:

Black Caribbean immigrants and their children contribute to improving the Black experience in the US by taking an active role in dismantling barriers that plague all Black people.

Jamaicans and Haitians make up two thirds of Black Caribbean immigrants and 9 out of 10 Black Caribbean immigrants live on the East coast.

Since the 1950s, a combination of low economic opportunities, political instability, crime and natural disasters have pushed thousands out of the Caribbean. In the US, the number of people born in the Caribbean who identifies as Black totals 2,083,488, representing 44% of all Black immigrants in the US. Jamaicans and Haitians make up two thirds of Black Caribbean immigrants, followed by Trinidadians, Dominicans, and in smaller numbers Barbadians, Cubans, Grenadians and Bahamians.

You may wonder why I’m emphasizing this data, and the connections between us Black folks here, those in the Caribbean, and Caribbean Americans. During the 2020 election cycle and this last one as well, there were a series of right-wing-funded attacks perpetrated against Vice President Kamala Harris questioning her “blackness,” though she has a Black Jamaican father. Alongside of that, Caribbean Americans were also dubbed not “Black Americans” by groups like ADOS and their social media followers.

Liz Dunn wrote for Left Voice:

ADOS, or American Descendants of Slavery, is a group founded by Yvette Carnell and Antonio Moore that is ”in favor of reparations for the descendants of slaves who were held in captivity in the United States, affirmative action for slavery descendants, and government subsidy of education and health care.” Their strategy involves differentiating themselves from non-American Black people, including more recent immigrants who have suffered and resisted alongside us for generations. For them, reparations are based on a specific kind of American identity, and ”Black immigrants should be barred from accessing affirmative action and other set asides intended for ADOS, as should Asians, Latinos, white women, and other ‘minority’ groups.” While addressing the issues Black Americans face in their specificity is important, doing so by scapegoating other marginalized groups and aligning with white supremacists is a misstep.

According to Media Matters, co-founder of ADOS Yvette Carnell is a board member for Progressives for Immigration Reform, which has been identified by the SPLC as a front for the far-right group Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR). FAIR has supported Trump’s border wall, mass deportations, concentration camps, and other violent and racist policies. Carnell, by associating with white supremacist groups, is pushing for material gains for Black Americans by targeting undocumented people.

In 2020, in response to ADOS, Black social media influencers like Reecie Colbert were quick to point out the names of some of our illustrious Caribbean Americans such as Malcolm X, Shirley Chisholm, Marcus Garvey, Stokely Carmichael, Sidney Poitier, and others.

We recently featured President Joe Biden’s pardon of Marcus Garvey, and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s ties to the Caribbean.

As we gear up for the battle to take back the House and the Senate in 2026, alongside the election struggles in state legislatures, and local elections, we need more solidarity, not less. We have to push much more forcefully to support those most affected by the right-wing push to destroy birthright citizenship.

While a majority of media attention has been focused on our southern border, we must not forget the plight of undocumented (and documented) Caribbean nationals and their children in other parts of the country. The recent detention of a Puerto Rican military vet in an ICE raid in Newark, New Jersey, has raised more concerns, since Puerto Ricans are American citizens.

I raised these same concerns about right-wing funded divisiveness in 2022 multiple times. I feel it is important to repeat them, and I plan to keep doing so.

Though Black History Month is celebrated in our shortest month, and in other times of the year elsewhere in the world (it’s in October in the UK), Black history is foundational to our history all year round. We should work to ensure that the role of the Caribbean and Caribbean Americans are always included.

Join me in the comments section below to discuss and for the weekly Caribbean News roundup.

I’m curious. What Caribbean Black history did you learn in school?

Campaign Action

)

)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·